MUSEUM OF MINERALOGY AND LITOLOGY

Università di Firenze, Via La Pira 4, 50121 Firenze, Italy

SECTION OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORENCE

Just as with the artistic collections in Florence, the Medici family was also responsible for the creation of the scientific ones. Over the centuries, the accumulation of the scientific specimens continued to grow through gifts presented by important visitors to the Grand Dukes or purchased from noble families, and through the ducal commissioning of collections from naturalists.

After the Medici family died out in the mid-eighteenth century, the Habsburgs-Lorraine became the Grand Dukes of Tuscany. Despite the will left by Anna Maria Luisa dei Medici, much of this precious material was dispersed in gifts to sovereigns or in public sales (these sales had already begun under the last Medici Duke, Gian Gastone). But at the same time there was a growing interest in naturalistic studies in keeping with the enlightened views of house of Lorraine. In 1763 Targioni Tozzetti was commissioned to inventory the collections in the grand ducal Wunderkammer, the Treasure Room in the "Uffizi and in the Pitti Palace".

Then, in 1775, the Grand Duke Peter Leopold decreed the creation of the Imperial Royal Museum of Physics and natural History, also called "La Specola" after the construction there in 1789 of an Astronomical Observatory, which was to remain on the site for almost a century.

In 1807, during the reign of Maria Luisa Borbone Parma, university level instruction in the sciences initiated in the "Liceo di Scienze Fisiche e Naturali", the direct fore father of the present-day Faculty of Mathematics Physics and Natural Sciences.

The I.R. Museum was housed in a building in via Romana, near the city gate and close to the royal palace.

The Museum was then opened to the public and those collections which had formerly been contained in the Wunderkammer (Treasure Room) as objects of curiosity and study were now placed on public view. The distinguished chemist and physiologist, Felice Fontana. He was appointed its first director. A former professor at the University of Pisa, Fontana notably enriched the collections taking advantage of his long voyages abroad and organised both the exhibitions and services of the Museum. Of primary importance is the ceroplastic workshop, specialised in the making of wax models of human and comparative anatomy and of botanical specimens which still today describe our admiration for their fidelity and aesthetic taste.

From the early years of the Restoration until the mid-nineteenth century these facilities underwent many vicissitudes such as the closing down and the eventual reopening, not only of the courses of' instruction but also of the Museum itself . The increased size of the collections and the institution of "chairs" for the various disciplines resulted in the splitting up of the Museum of Physics and Natural History into several museums and "cabinets", as they were then called, scattered in various parts of the city.

In 1 880 the Mineralogy and Geology Section of the Museum of Physics and Natural History was transferred from Via Romana to its present location in Piazza San Marco, where the "Museum and Laboratory of Mineralogy" was established under the direction of Prof G. Grattarola.

By 1925 the Museum of Mineralogy had expanded to approximately 2,000 sq.m., but subsequent demands to make room for new research laboratories led to various changes until, in 1973, the Museum had shrunk to only 380 sq.m.

The great number of specimens has increased substantially through the acquisition of new material. The high scientific and historical value of the collections make the Museum of Mineralogy of the University of Florence perhaps the most important mineralogical museum in Italy and one of the most widely-known abroad.

The Museum's more than 45,000 specimens are divided into six major collections as follows: the General Collection, the Italian Regional Collection, the Island of Elba Collection, Worked Stones and Gemstones, Meteorites and the Targioni Tozzetti Collection.

The General Collection consists of about 23,000 specimens from all over the world, gathered together and catalogued according to the traditional classification used for minerals, that is, according to their chemical composition. The core of this collection goes back to the early 1700s and has grown considerably through purchases and gifts, not only of individual specimens but also of entire collections, such as those of Ciampi and Capacci. Most recently the collections Ponis and Giazotto, along with the micromount collection Koekkoek, have been acquired by the Museum.

The Regional Collection encompasses specimens from Tuscany, Sicily and Sardinia, many of which of the Brizzi collection, recently donated.

The Museum of Mineralogy owns the most important and comprehensive collection of minerals from the Island of Elba (approximately 6,500 specimens), mainly the result of the merger of two collections acquired by the Museum from Foresi and Roster around 1880.

The value of the Worked Stones Collection is essentially historical and aesthetic.

It contains about 700 specimens, all from the Medici family. These objects come from the Uffizi Gallery and were destined for the Royal Imperial Museum of Physics and Natural History. The craftsmanship of cups, bowls, snuff-boxes, plates, small pots, and vases has been attributed, for the most part, to the workshops of the Gallery. Only the jade objects were made in the Orient.

The Meteorite Collection is more modest, containing approximately 80 specimens from various places. The Italian meteorites whose fall was verified at the time by eyewitnesses are especially interesting: the oldest one fell in the province of Siena on June 16, 1794.

The Targioni Tozzetti Collection is of great interest from both a scientific and especially a historical point of view, since it was established in the mid- 1700s. This collection of approximately 5,000 pieces is complete with the original catalogue manuscripts and drawings by Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti, continued after his death in 1 783 by his son Ottaviano. Unfortunately, due to lack of space, this collection is not on public display.

In addition to the Mineralogy and Lithology Collections, the Museum Library with more than 500 volumes is also worth mentioning. It contains numerous ancient texts, among which several editions from the 1500s and a collection of old scientific instruments and devices.

Visitors to the Museum can refer to the recommended itinerary shown on the floor plan of the exhibits.

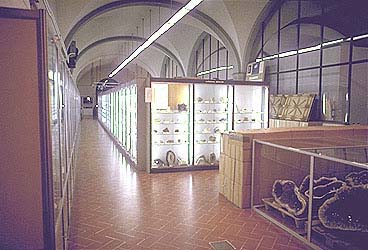

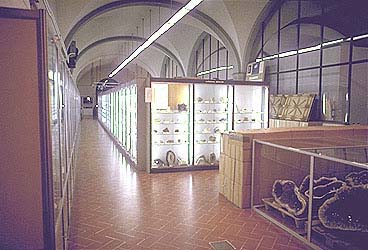

The current exhibit space, besides that in the main Exhibition Hall (sector 1) with the oversized specimens, extends into a spacious room where there is a row of a hundred or so showcases containing a smal1 part of specimens belonging to the various collections. This display is in the process of being rearranged, starting from one side with the preparation of a row of show-cases for didactic purpose, and continuing on to the other side where several cases are being renovated in order to put the available space to better use.

Upon entering the main Exhibition Hall, the visitor first encounters the collection of enormous amethyst quartz geodes from Brazil, the biggest of which weighs 380 kg. (sector 2). On the right (sector 3), the amazing specimens of tourmaline and beryl which come from the pegmatitic formations of Brazil can be admired. There are illustrations on the display cases containing the samples which show the characteristics and properties of these minerals. The large hexagonal crystals of pink beryl (the morganite variety) associated with acicular tourmaline, quartz, and albite are of particular interest, along with the tourmaline crystals of remarkable beauty and perfection, in typical condors: from green, blue, and pink, to the gorgeous red specimens of the rubellite variety

In sector 4 of the Exhibition Hall, show-cases with didactic and illustrative material are in the process of being prepared in order to better help the visitor understand the world of minerals, from the definitions of rock, mineral, and crystal structure, to that of mineralogical species and varieties.

Some space is also dedicated to meteorites: besides the definition and classification, several examples are on display, among them a 28-kg. specimen which fell in 1896 in Chupaderos, Durango, Mexico.

Next, after some show-cases dedicated to the genesis of minerals, there is a show-case dedicated to crystallography, with examples of the elements of symmetry and illustrations of the seven systems in which minerals can crystallise. A row of cases follows, showing the physical properties (such as density, hardness, fracture and cleavage, and colour) and the optical properties of minerals. Finally, there is a case dedicated to both synthetic and artificial precious stones, where, along with schematic drawings of the synthesis processes of corundum and "cubic zirconia," synthetic precious stones obtained through various techniques are displayed.

In sector 5, some enormous crystals of minerals which are typical of Brazilian pegmatites are of considerable interest and beauty. On display are: a specimen of orthoclase with tourmaline, albite, and lepidolite mica weighing 105 kg.; a 135-kg. smoky quartz with exceptionally well-developed faces; a twin crystal of aquamarine beryl weighing 82 kg.; and a 180-kg. morion quartz with single crystals more than one meter long. A large tourmaline crystal, weighing 150 kgf, with quartz, orthoclase, albite, and lepidolite mica is of special interest.

Worked stones and gems are located in sector 6. The cases in the left corner hold a selection of specimens from the Medici collection: the large boat called the "salad-bowl" in hyaline quartz; a small vase also made from quartz, engraved with mythological figures; bowls made from agate, jasper, and lapis-lazuli, some of which bear the engraved letters LAURMED, for Lorenzo dei Medici, and others with the initials and dates F.M. 1582 and F.M. 1600, for Francesco I and Ferdinando I.

Also in this exhibit are: dogs' heads (one in onyx and one in amethyst) of Aztec origin; snuff-boxes made from various valuable minerals; small pots for cosmetics from jasper; small obelisks and vases in fluorspar; and small statues in jade and other "cut stones"

Gems and precious stones are displayed in the right corner. Two rough specimens stand out in particular: a topaz crystal weighing 151 kg. (the second largest in the world), which comes from Minas Gerais, Brazil; and a 98-kg. aquamarine beryl, also from Minas Gerais. Other precious stones are exhibited as well, in some cases both the gem and the rough crystal. The items have been arranged according to their hardness from diamonds, among which a perfect 20-carat octahedron stands out, to corundum (ruby and sapphire varieties); from beryl (emerald and aquamarine) to topaz, and so forth on to the less hard stones. Lastly, there is a case with hard stones and ornamental stones, the upper part of which is filled with various types of quartz Above the case with the gems, there is illustrated information on hard and ornamental precious stones, with schematic drawings showing the cutting of gemstones, in particular diamonds.

The collection from the Island of Elba occupies sector 7. The minerals from the deposits in Rio Marina and Capo Calamita are represented by: beautiful hematite crystals of different varieties; concretions and stalactitic masses variegated with limonite; pyrite aggregates and perfect magnetite crystals; and by an exceptional specimen of ilvaite. The amazing specimens of granitic rock from the area around S. Piero, however, are unique in all the world; particularly noteworthy are the four enormous blocks and geodes covered with pegmatitic minerals like pink beryl, tourmalines of various colours, and the very rare pollucite, in addition to quartz, orthoclase, and albite.

The show-cases in sector 8 are dedicated to the General Collection, including specimens from all over the world, divided into ten classes according to their chemical composition.

The General Collection ends with display cases dedicated to holotypes, i.e. those specimens from which a new mineral has been identified for the first tome in Florence. These have been registered at the Museum as required by the I.M.A. (International Mineralogical Association) in order to recognise a new mineral species. Up today the holotypes registered at the Museum are 23.

Sector 9 is dedicated to the Tuscan Regional Collection, represented by numerous specimens of great interest from the various mineralizations in Tuscany, such as sulphur from Sasso Pisano, sphalerite, stibnite, and gypsum from the area around Grosseto, cinnabar from Mt. Amiata, and pyrite from Gavorrano. The sphalerites and chalcopyrites from the Bottino di Seravezza mine in the Apuan Alps are remarkable for their beauty.

Sector 10 has show-cases dedicated to Sicily, with crystals of sulphur, noteworthy for their colour and beauty, along with celestite, aragonite, calcite, and gypsum representing the characteristic minerals of the island. Continuing on to Sardinia, the specimens of covellite, cerussite, and azurite are of great aesthetic value, unique for their crystallisation and the perfection of the crystals. The specimens of malachite and phosgenite, along with a large specimen of barite from Silius, are of particular interest.

Some show-cases (sector 11) home special exhibits.